Navigating the Social Security filing process as a single individual can be a daunting task. The considerations you need to make differ significantly from those of married couples. In this guide, we aim to simplify this process and provide you with the essential information you need before filing for Social Security. It’s crucial to get this right, especially as a single individual, as there’s no safety net of a spouse’s income or assets.

As a single person, your retirement planning process is distinct from that of married couples. While some considerations overlap, their significance varies. Additionally, there are unique factors that only single individuals need to consider. This guide is designed to help you navigate the complexities of filing for Social Security as a single person, whether you’ve never been married, are divorced, or are widowed.

We’ve broken down the decision-making process into four key areas: Prior Marriages, Life Expectancy, Retirement Income Need, and Other Assets and Income.

1) Prior Marriages: If you were previously married, you might be eligible for spousal or survivor benefits.

2) Life Expectancy: This factor is used to calculate a break-even analysis, which is crucial in determining the best time to start receiving benefits.

3) Retirement Income Need: Understanding your monthly income requirement in retirement is vital to ensure that your Social Security benefits, along with other income sources, can meet your needs.

4) Other Assets and Income: If you have other retirement savings, your Social Security filing strategy will need to coordinate with your withdrawal strategy from these accounts.

Now let’s dive into more details for each of these consideration points and discuss how each may be applied.

Consideration #1) Spousal or Survivor Benefits

Even if you’re single now, you may still be eligible for spousal or survivor benefits based on a previous marriage. The Social Security system has provisions that allow for such benefits under certain conditions.

To be eligible for a spousal benefit, you must have been in a marriage that lasted at least 10 years before ending in divorce. This benefit is based on the earning record of your ex-spouse, and it can provide a significant boost to your retirement income, especially if your ex-spouse was the higher earner.

Survivor benefits, on the other hand, are a bit different. These benefits can be paid if you were married for at least 10 years before divorcing, or if you were married for at least 9 months at the time of your spouse’s death. Survivor benefits are designed to provide financial support to the surviving spouse based on the deceased spouse’s earning record.

It’s important to note that there are exceptions to these rules. For instance, if a spouse passes away after a marriage that lasted less than 9 months, the surviving spouse may still be eligible for survivor benefits under certain circumstances. These exceptions are detailed in the article “Survivors’ Benefits: Exceptions to the Marriage Length Requirement.”

One key aspect to consider, particularly in the case of survivor benefits, is the timing of when you choose to file. You have the option to file for a survivor benefit as early as age 60, while allowing your own benefit to continue growing until age 70. This strategy can be highly beneficial in the right circumstances, potentially leading to a significant increase in the total amount of benefits you receive over your lifetime.

So even if you’re single now, your marital history could play a significant role in your Social Security benefits. Understanding these nuances can help you make informed decisions that optimize your retirement income.

Consideration #2) Life Expectancy

The second factor to consider when deciding when to file for Social Security benefits is your life expectancy. While I don’t advocate for using this factor in isolation to make this decision, it does play a significant role, especially for single individuals. As a single person, you don’t have to consider the survivor benefit you would leave behind for a spouse, which simplifies the decision-making process to some extent.

One common method of incorporating life expectancy into your decision is through a break-even analysis. This analysis compares the total value of receiving lower benefits earlier versus the total value of receiving higher benefits later. For instance, if you choose to start receiving benefits at 62 instead of waiting until 67, you’ll receive five years’ worth of benefits before you would have if you waited until 67. However, your monthly benefit will be significantly lower once you reach 67.

Therefore, you need to live past a certain age, known as the “break-even age,” to make the decision to delay collecting benefits until 67 financially worthwhile. We’ve developed a simple and free-to-use break-even calculator to assist you in figuring this out. If you’re interested in a more comprehensive tool, consider using software like “Maximize My Social Security” or the “RSSA Roadmap.”

In addition to these tools, you might want to use an external resource to estimate your statistical life expectancy. The Social Security Administration’s Life Expectancy Calculator is a reliable tool for this purpose. It’s important to remember that these are just tools and estimates. Your actual life expectancy can be influenced by many factors, including your health, lifestyle, and family history.

Consideration #3) Retirement Income Need

The third factor to consider, and arguably the most crucial one, is your monthly net income need. This is the total income you need to be deposited into your bank account every month during your retirement. Understanding this number is vital because it forms the basis of your retirement income plan. Your monthly net income need, minus your Social Security benefit, is the deficit that must be met with other income sources. Knowing this deficit amount is critical to formulating the right filing strategy for Social Security.

If you don’t know this number, you risk filing for Social Security at the wrong time, which could result in a permanently reduced benefit that may not be sufficient to meet your retirement income goal. Therefore, it’s essential to determine your monthly net income goal before you file for Social Security.

Fortunately, figuring out this number isn’t as daunting as it might seem. My team has developed a calculator designed to help you arrive at this number without the need for complicated spreadsheets or averaging your expenses over the last five years. This tool simplifies the process, making it easier for you to understand your retirement budget.

Our retirement budget calculator is available for you to use for free and without any hassle. There’s no need to provide your email address, log in, or navigate through any other obstacles.

Consideration #4) Other Assets and Income

The final point to consider, particularly if you have retirement savings in a 401K or other retirement account, is how your Social Security filing strategy will interact with your other assets. Having savings gives you the flexibility to create a strategic plan that coordinates withdrawals from your retirement accounts with your Social Security benefits. If done correctly, this strategy can lead to significant tax savings and help preserve your account balances.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. Consider Lisa, who has a Full Retirement Age (FRA) benefit of $2,750 and $500,000 in her IRA. She wants a total net retirement income of $4,000 per month. The question then arises: should she file for Social Security at 62 and supplement her income with withdrawals from her IRA, or should she delay filing for benefits, which would mean she would need to draw all of her income from her IRA until she files for Social Security?

To understand the implications of each choice, let’s look at how the numbers would play out in today’s dollars. Of course, these figures would be adjusted for inflation and taxes, so they’re not exact, but they provide a clear picture of the potential outcomes.

Lisa wants $4,000 per month in retirement income.

- If her full retirement age benefit is $2,750, she would need to withdraw $1,250 per month from her IRA.

- If she files at 62, she would receive $1,925 from Social Security and would need to withdraw $2,075 from her IRA.

- If she files at 70, she would receive $3,630 from Social Security and would only need to withdraw $370 from her IRA.

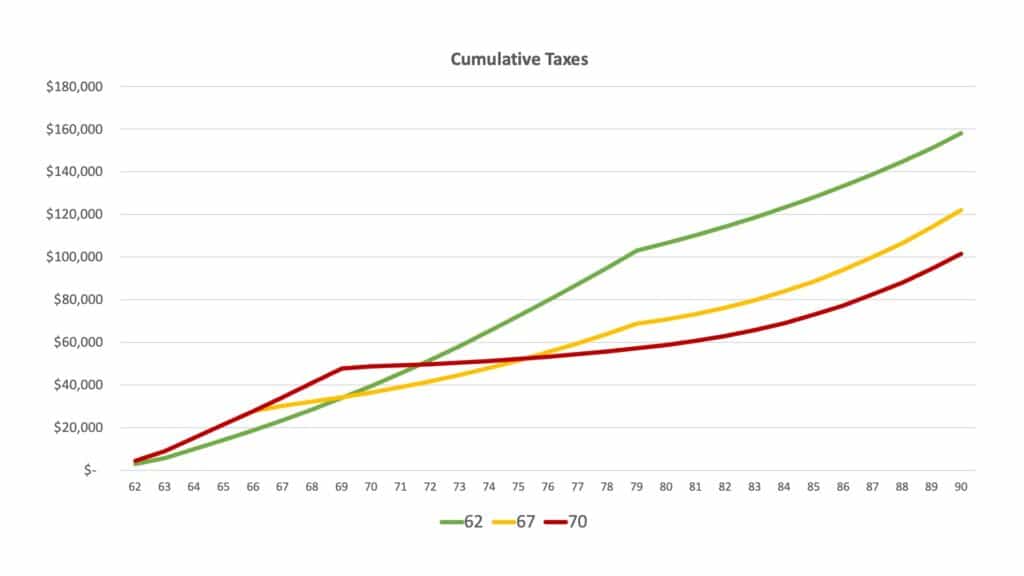

To simplify this, let’s look at the Social Security filing decision based on three filing ages: 62, 67 (or full retirement age), and 70. We’ll focus on how filing at these different ages would affect her taxes and her account balances.

First, let’s examine the cumulative taxes throughout retirement. Keep in mind that the net income is the same in each case and is adjusted for inflation every year. The only variable here is the Social Security filing age. If Lisa files at 62, she initially has the lowest tax cost because some of her income is coming from the IRA, and a good part is coming from Social Security, which is partially tax-free. However, by about age 69, the cumulative tax cost for filing at 62 exceeds the cost for both filing at 67 and at 70. By age 71, the tax cost for having filed at 62 will exceed the cost for filing at 70. By age 80, the difference is just over $47,000, and by 85, that difference is $55,000.

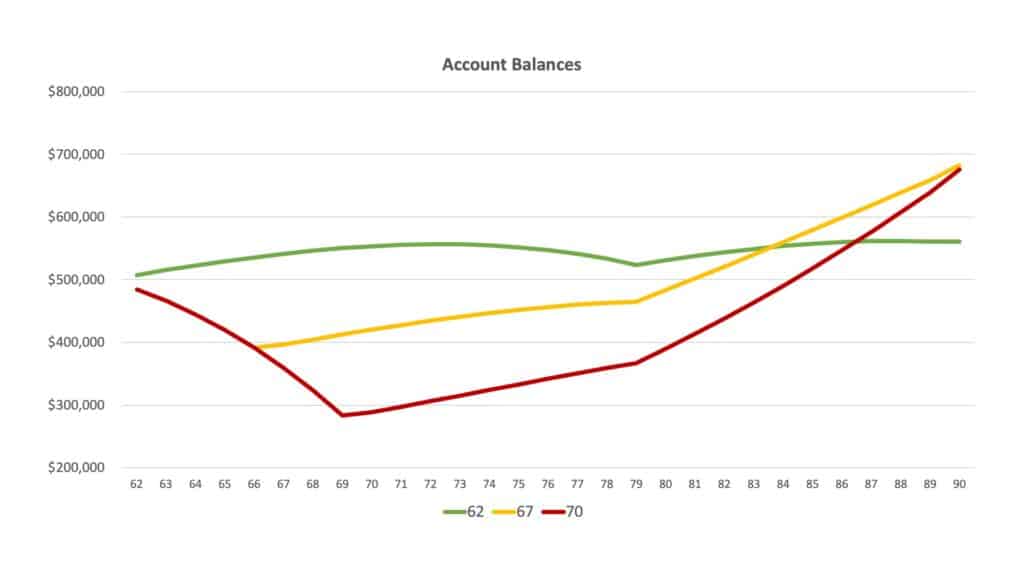

The tax cost of the various filing strategies is certainly a factor to consider, but there’s another equally, if not more, important data point: how do the filing strategies affect the IRA balances? Do any of them ever run the risk of depleting the account?

If Lisa files at 62, there’s never a significant drawdown from the IRA because a large part of her income is coming from Social Security, so the account value stays fairly level throughout her retirement. But if she delays until 67, there is a decline between 62 and 67 of about $100,000. That’s because she does not have any income from Social Security, and the IRA is bearing the load of all the retirement income. However, once Social Security kicks in, and the withdrawal amount is less, the growth slowly starts exceeding the withdrawals. At around age 84, the balance catches back up to where it would be if she had filed at 62.

If she files at 70, the immediate decline is much deeper because she is drawing all ofher income from her savings for a longer period of time. In this case, the portfolio value drops by over $200,000, and it takes until age 87 for the balance to catch up with what it would have been if she had filed at 62.

Here’s another point to ponder: how comfortable would you be with nearly half of your portfolio being used to increase your Social Security benefit? For some, the assurance of a larger Social Security benefit in the long run would be worth it. For others, this approach might feel too close to depleting their accounts. This is a personal decision, and it’s important to consider your comfort level with risk.

Remember, these calculations are based on linear rates of return. In reality, the market fluctuates, and there could be negative years. If things don’t go perfectly in those years between 62 and 70, the situation could become challenging.

The key takeaway here is that retirement planning is a blend of data and emotion. You need to gather the data, then determine how you feel about it. Some might prefer filing at 70 purely for the tax savings, while others might balk at the idea of spending their IRA just to get a larger Social Security benefit. Your personal feelings about these scenarios are up to you, but first, you need to gather the data.

That’s where we can help. If you want to ensure that your plan won’t cost you too much in taxes and won’t expose you to excessive risk, we can assist you. The charts you just saw, and many more, are included in every plan we create. If you’re interested in gaining clarity about your retirement plan, you can use this link and schedule a call directly with us.